India’s Regulatory Overkill on Gold Loans

Back in March of this year, when the Reserve Bank of India stepped in with a cap of 60% on the loan to value (LTV) ratio for gold loan NBFCs, it said it was acting to pre-empt systemic risks and to safeguard public funds. The verdict was that the gold loan companies depended too much on public funds and their focus on a single product made them vulnerable to concentration risks. Moreover, there was unease about the big players in the business growing too fast, and fears of a bubble building up in the sector.

Back in March of this year, when the Reserve Bank of India stepped in with a cap of 60% on the loan to value (LTV) ratio for gold loan NBFCs, it said it was acting to pre-empt systemic risks and to safeguard public funds. The verdict was that the gold loan companies depended too much on public funds and their focus on a single product made them vulnerable to concentration risks. Moreover, there was unease about the big players in the business growing too fast, and fears of a bubble building up in the sector.

As with all major policy changes, a final judgment is best reserved until the consequences, intended and unintended, have played out fully. However, more than six months down the line, the initial assessment is not promising, pointing as it does to an element of overkill.

Concentration risk in perspective

The Housing Development Finance Corporation (HDFC) is one of the most successful companies in the financial sector today, widely regarded as a blue-chip. HDFC deals in loans to the real estate sector, mainly individual housing loans, and has built up a loan book of nearly Rs.150,000 crores backed by substantial borrowings from the public and the banking system. Housing loans are typically given out for long tenures of ten to twenty years even as the market remains vulnerable to cyclical downturns. In fact, the recent international experience with loans against real estate has been none too happy, with the downturn in the US realty market being the proximate cause for the financial meltdown of 2008. However, in India, HDFC continues to stand tall.

Shriram Transport Finance Corporation Ltd. lends mostly against second hand trucks. The company has assets under management (AUM) of over Rs.40,000 crores, substantially funded by banks. Unlike real estate or gold, a truck is a rapidly depreciating asset whose whereabouts are hard to keep track of. But, thanks to the many innovations thrown up by its focused model, this is not an issue of concern. Today, the company is hailed as a pioneer in truck finance whose efforts have transformed thousands of humble truck drivers into proud truck owners.

From a regulatory perspective, both HDFC and Shriram Transport would appear to represent instances of concentration risk. However, from a business perspective, these are examples of the theory of core competence put into successful practice. The focus on a single product gives their management extra insights into the nitty-gritty of the business. In turn, it enables innovations that help in containing risks in the business. That’s why, even as concentration risk appears to increase, a host of other risks are actually contained, and the business is stronger for the focus.

Anomalies

As widely noted in the media response, the cap on LTV reduces the usefulness of gold as a financial asset that can be used in times of need. In fact, it hurts the poor who are now forced to borrow from the unorganised sector on more adverse terms. The irony that the RBI, of all institutions, should work to give a new lease of life to India’s old school pawnbrokers and moneylenders did not go unnoticed. Indeed, something similar is already playing out in Andhra Pradesh where media reports speak of usurious moneylenders back in business with a bang now that microfinance players have been silenced.

Further, as things stand, it’s possible to obtain 80 percent finance against a vehicle which sheds 30 percent of its value in the very first year. In a gold loan where the underlying security is immune to depreciation, you get only 60 percent. Existing regulations permit NBFCs to extend unsecured loans to their customers. In this context, expressly forbidding gold loan NBFCs to lend beyond a defined cap on LTV appears to defy logic. If lending without security is permissible, surely lending against security at a low margin should also be permissible.

Besides, a uniformly low LTV artificially levels the playing field to the point of the lowest common denominator. It denies the established players a legitimate opportunity to capitalise on their experience and superior risk management practices. After all, gold loans at higher LTVs are sustainable only if the company possesses adequate risk management skills to handle defaults and price corrections.

Required, a recalibration

That the RBI has acted out of its responsibility to prevent critical risks from materialising is not in question. But what has fallen off the radar is a recognition of the potentially transformative impact of gold loans, particularly in monetising India’s vast stock of private gold, and in advancing financial inclusion (about 65% of our gold is held by rural India). By restricting LTV to 60% and selectively applying it to gold loan NBFCs, there’s the risk of stifling the original innovators in the business, and of needlessly reinvigorating the unorganised sector. Indeed, the RBI would do well to keep an eye out for the flip side of it all, and not hesitate to recalibrate its policy responses when the evidence calls for it.

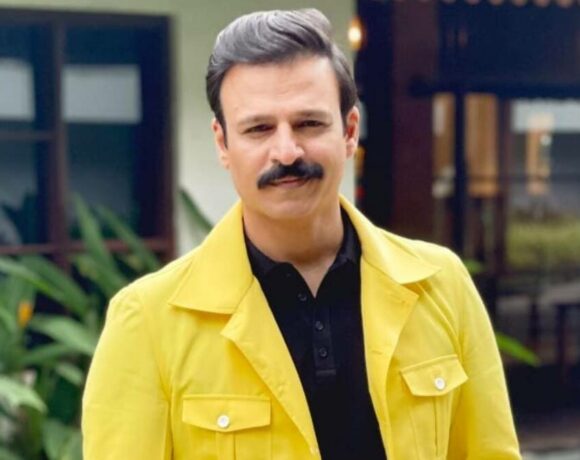

(Shri V.P. Nandakumar is MD & CEO of Manappuram Finance Ltd.)