CONCENTRATION RISKS IN GOLD LOANS OVERSTATED

India’s gold loans NBFCs have been in the news a lot lately. For long a business ignored by all, public interest perked up as stories about handsome gains in the shareholder wealth of Manappuram Finance made news. It peaked around April-May 2011, when Muthoot Finance had its highly successful IPO.

India’s gold loans NBFCs have been in the news a lot lately. For long a business ignored by all, public interest perked up as stories about handsome gains in the shareholder wealth of Manappuram Finance made news. It peaked around April-May 2011, when Muthoot Finance had its highly successful IPO.

Later, the focus shifted to the blistering pace of growth of these companies, and questions began to be asked about how sustainable it was. In March 2012, the RBI stepped in with sweeping measures that pretty much took the fizz out of the business. At the top of RBI’s concerns about the gold loan NBFCs was the concentration risk inherent in the business model, brought into sharper focus by the sector’s phenomenal growth. In the three years between 2009 and 2012, the total asset size of the gold loan NBFCs increased sharply from Rs.54.8 billion to Rs. 445.1 billion.

The basic idea of concentration risk is not new and is neatly captured in the proverb, “Don’t put all your eggs in one basket.” The world woke up to the consequences of concentration risk during the sub-prime meltdown in the US in 2008. The important lesson was that concentration risk applied even to sectors where conventional wisdom would deny the possibility of an adverse outcome based on a conviction that if something has not happened before, it won’t happen in future too. For over three decades, residential property prices in the US kept going up. To the banks dealing in mortgage loans, it simply did not occur that the value of their collateral would fall below the loan outstanding. And yet it did, in a way that’s been called a black swan event, which is to say, a probability of occurrence as rare as sighting a black swan, but massive in impact. What began as troubles with sub-prime mortgages went on to become the worst recession in post-war US history.

Around this time, questions began to be asked in India about how susceptible we were to a similar sequence of events. After all, in the decade before, the housing loans portfolio had multiplied manifold at India’s banks, driven by the example and aggression of private sector players like ICICI Bank and HDFC. The Indian scenario also had other similarities with the US. One reason why US housing attracted so much investment in the run-up to the crisis was the generous tax incentives made available, based on a national consensus that home ownership is inherently desirable, and to be encouraged. This is true of India as well, and our tax code allows many deductions and exemptions for home loans. Consequently, the banking sector’s exposure to home loans had gone up substantially and real estate prices showed a firm upward trend. The word in the market was that it was all booming.

For all the overt similarities, for once, there was no panic, no knee-jerk reaction. It was concluded that the Indian scenario was rather different, no need to press the panic button.

Firstly, from a purely banker’s point of view, it was pointed out that thanks to the nature of the real estate business in India—a significant “black money” component is the norm in most real estate deals—the price of the property would be significantly under-reported and undervalued. Therefore, there is more cushion available to lenders than would appear on paper, and borrowers would have a greater incentive to keep their accounts in good standing.

The second factor had to do with our social and cultural norms. Family ties are stronger in India and the socio-cultural values that bind a family together also finds expression as an emotional connect with the family home. Home owners are unlikely to stop repaying their home loans just because home prices have fallen and the equity on their mortgage goes into negative territory.

While fears about concentration risks in the Indian housing loans segment were determined to be premature, it’s unfortunate that similar factors at play in gold loans are not given due consideration. After all, in trying to get a measure of the risks in gold loans, interesting points of similarity with housing finance emerge. Exactly in the way that the black component in real estate deals results in undervaluation of property, so too does the making charge add to the security of the lender in gold loans. Because making charges are not financed even as it gets priced into all purchases of gold jewellery, it’s a hidden cushion to the lender in the way that the black money component in a real estate transaction is.

Further, precisely as stronger family ties bind people to their homes, they are also emotionally attached to the family jewellery. Often, the jewellery is in the nature of a family heirloom, acquired during important occasions like a marriage, or the birth of a child etc. More often, it belongs to the women in the family who are loath to let it go. Over the years, our experience has been that occasions of wilful default, especially with intention to capitalise on fluctuations in gold prices, are very limited.

Clearly, then, the extra cushion given by circumstance to India’s housing loan financiers, which sets them apart from their peers in the US, applies to gold loans as well. What is needed now is simply a greater recognition of this reality from official quarters. What we don’t need is premature alarmism.

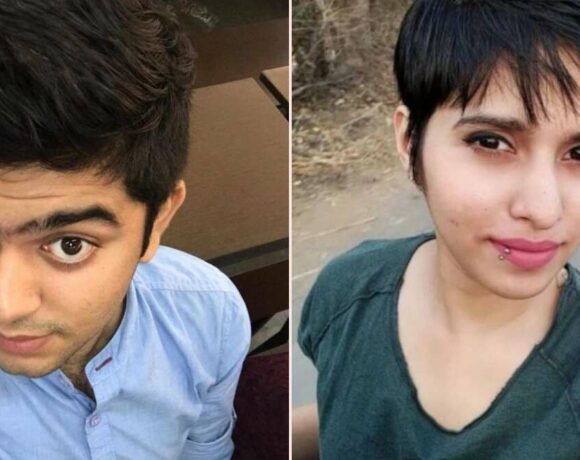

V.P. Nandakumar

MD & CEO of Manappuram

Finance Ltd., a leading gold loans company